WOODLAND, Wash. — A Woodland woman is approaching the one-year anniversary of a rare milestone: In December 2018, Emily LeFrancq had her stomach removed.

Now she's tackling her new life with grace and optimism, and she credits her late father for that.

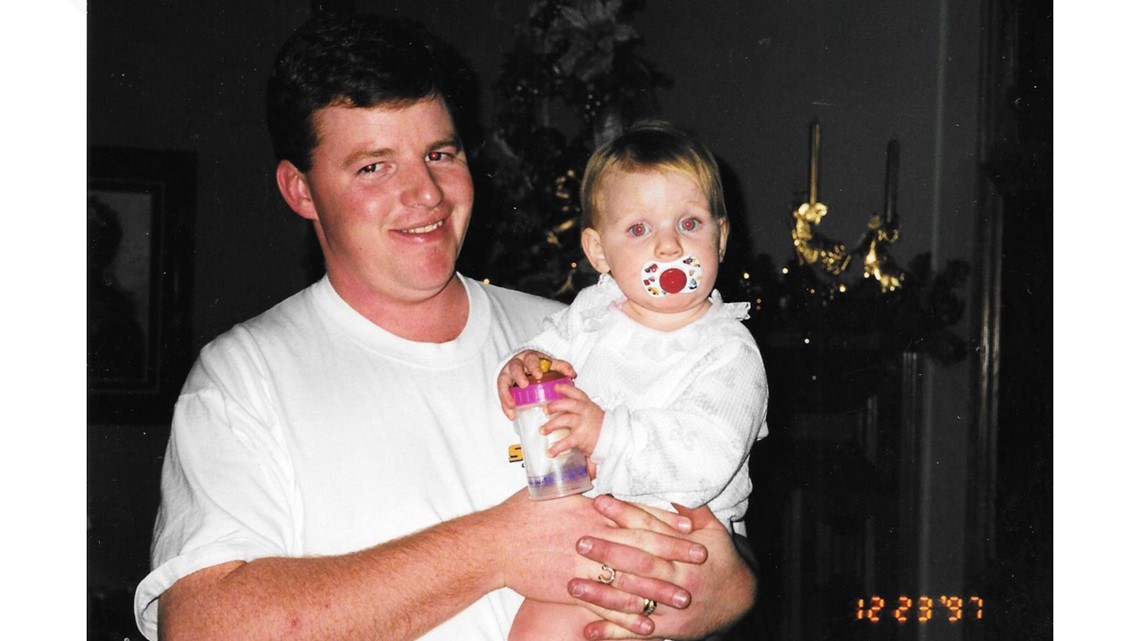

“My dad was the kindest person I ever met,” she said.

LeFrancq’s father died from brain cancer in spring of this year.

“He battled for five years and fought so hard and he lived a great life.”

LeFrancq says as her father battled brain cancer, tests revealed he had a mutation in his CDH1 gene. That mutation put him at risk for stomach cancer. But because his brain cancer was so advanced, there was nothing to do.

The gene mutation can be passed down within a family, so LeFrancq wasted no time getting herself tested. The tests came back positive: LeFrancq carried the CDH1 gene mutation.

“Right now they think if you have the gene you have up to an 80% chance of getting stomach cancer,” said LeFrancq.

LeFrancq wanted nothing to do with that, so she took matters into her own hands.

“I was going to get my stomach removed, no matter what.”

Research led LeFrancq to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, where she met Dr. Jeremy Davis.

“Once you’ve developed stomach cancer the likelihood of surviving it five years down the road is pretty low,” Davis said.

Dr. Davis and his team got right to work. During a procedure last December that took several hours, they removed LeFrancq’s stomach and connected her esophagus to her small intestine.

“Emily is in many ways a poster child for people with this problem,” said Dr. Davis. “She’s handled it really well.”

After removing LeFrancq's stomach, doctors discovered it was cancerous.

“It’s such a fast-moving cancer, and mine was already growing,” she said.

LeFrancq is now a lot healthier, even without a stomach.

“I don’t have a holding space for food," she said. "But the longer I go without having a stomach, my intestines will stretch over time. And that’ll give me a pouch on its own.”

LeFrancq can only eat small portions and she needs to stay away from too much sugar.

“I eat a lot of chicken and proteins and fish,” she said. “I try to feed my body with high protein meals.”

As time-consuming as it may be to make special meals, and to eat every two hours, it is the least she can do for herself. She knows the alternative is far worse.

“Realistically I probably wouldn’t have made it to my mid to late 20s if I didn’t know about this,” she said.

LeFrancq knows there will be tough days ahead. But she is excited about her future.

“I just hope that I can be … that people can look at me and say, 'If she can do it, I can do it too.'”

LeFrancq says the CDH1 gene mutation puts her at risk for breast cancer, too. So she has decided to get a double mastectomy.

Through it all LeFrancq has maintained an incredibly positive attitude, which is something else that runs in the family.

“I kind of credit my whole attitude to my dad,” she said.