PORTLAND, Ore. — Earlier this week, many around the world celebrated World Refugee Day — a day that falls on June 20 every year, internationally recognized by the United Nations.

This day symbolized many things for those who identify as refugees: a day of hope, reflection, remembrance and optimism. For one former Congolese refugee in Portland, this day hit close to home.

Joy Mulumba is the Executive Director of the African Family Holistic Health Organization (AFHHO), founded by his mother, Therese Lugano, in 2017. The organization was initially founded to provide resources and support to African mothers before, during and after pregnancy.

AFHHO has since grown to provide a plethora of resources such as rental assistance, wellness and mental health resources, food, clothing, parenting resources, networking opportunities, housing, translation services, English learning, advocates, maternal health resources, and a safe space for community members to hang out.

AFHHO initially provided these resources to Swahili-speaking African refugees and immigrants but over time has opened up their resources to all Black-identifying refugees and immigrants.

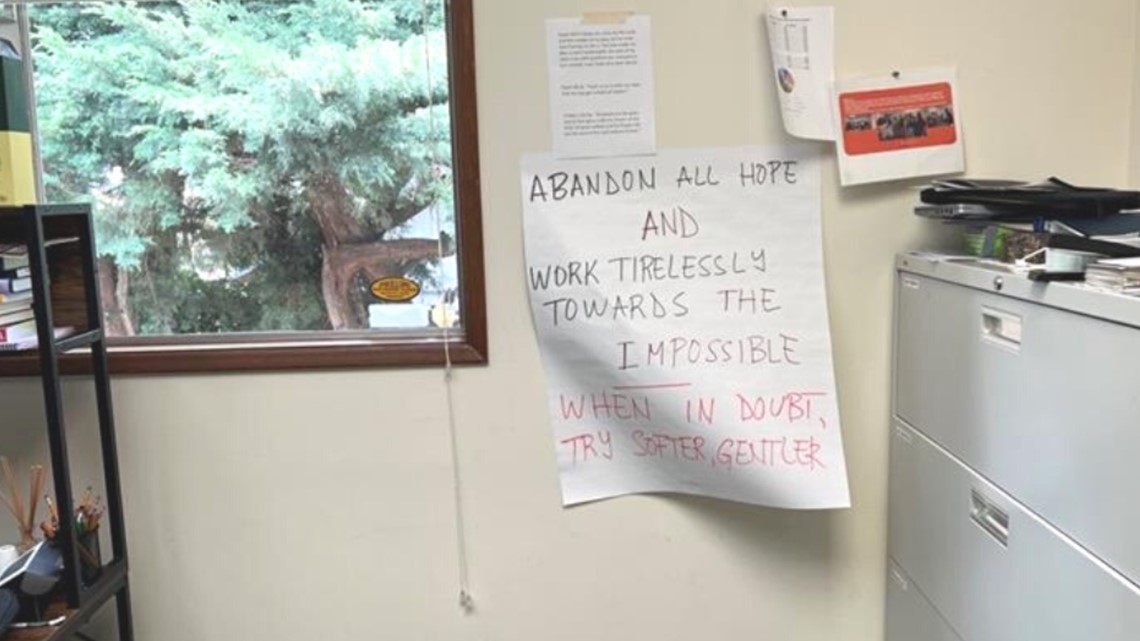

In Mulumba's office you'll see signs posted on the walls filled with uplifting Bible verses or quotes such as "Abandon all hope and work tirelessly towards the impossible" or "When in doubt, try softer, gentler."

These are mantras that Mulumba has learned to implement in his day-to-day life. Empathy is a theme that has been consistent for him working with African refugees and immigrants, as he was once in their shoes.

Growing up in Bukavu

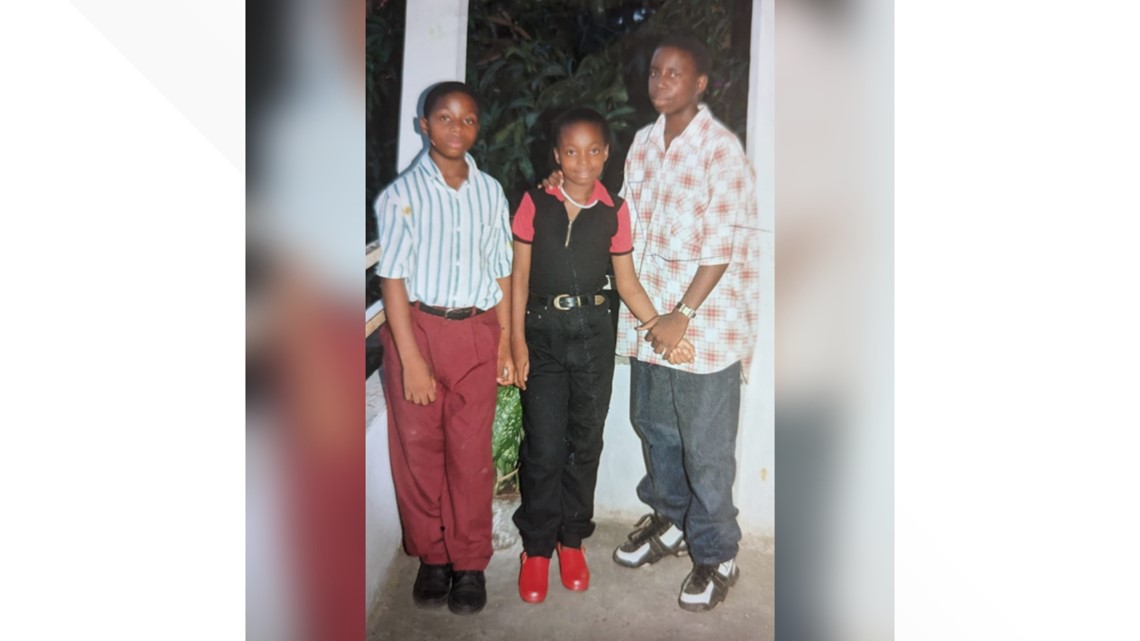

Mulumba was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo and was the oldest of three. His mother was a lawyer and senator while his father was an engineer.

"We were middle class and pretty well off. I was born in Kinshasa, but I grew up in Bukavu — those two cities, four hours apart. Bukavu is actually close to Rwanda," said Mulumba. "I grew up in Bukavu, that was from 1985 to 1997."

His parents ensured he and his siblings learned French as their first language, making Swahili and Lingala their secondary languages — putting them at an advantage.

"Being you know, from a privileged background, my parents were like — let's give you an advantage by teaching you French. French is my first language instead of Swahili and Lingala. Those are the other two languages I speak. But the Democratic Republic of Congo has more than 200 languages spoken," said Mulumba.

He described Bukavu as a small and safe town to grow up in.

"Everybody kind of knew each other and kind of knew who I was. You could walk two hours by yourself without being worried about anything safety wise," he said.

Tragedy struck his family in 1992 as his father passed away — leaving them in a world of pain and grief.

"You know, it was really tragic, and caused a lot of grief in the family," he said.

Mulumba and his family lived two hours away near Rwanda. In 1994, as they fearfully followed news of the Rwandan genocide, they started to prepare an escape plan.

More than 800,000 women, children and men were gruesomely killed when militias made up mainly of members of Rwanda’s Hutu ethnic group turned on their Tutsi neighbors during 100 days of horror in the East African nation in 1994.

"They were showing the bodies, decapitated bodies and mutilated bodies on TV, no editing or filters because there was no censoring of images at the time," Mulumba said. "It was pretty traumatic for a 10-year-old to be seeing these kind of gruesome images. My family had just had a conversation regarding us preparing ourselves for if things got worse, that we'll find a way to fly to Kinshasa, which is four hours away."

At the time, conversations around mental health or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder were non-existent, he said.

"Most people were not aware of how to have emotional language. So things you are just experiencing — the numbness, dissociation. I remember how much people were drinking to numb the pain and numb the feelings. Even shifting blame on those random refugees who were coming to our city and started blaming them. 'You are the ones, you must've angered God'. So they would start to say, 'You must have sin somehow, to bring the wrath of God on you'. They started bringing this religious interpretation that, 'You must have done something really bad for God to punish you. Like, there's no other way, you guys could be killing each other like that'," said Mulumba.

In 1997, his family became refugees desperately searching for a way out of the city. They were unable to fly out, as flights were no longer allowed out of Bukavu. Uncertainty and fear were constant feelings Mulumba and his family couldn't evade. They unexpectedly found refuge from other families in a village who were strangers to them.

"Those families in the village. We didn't know them. They didn't know us. They saw us and were like, 'Hey, do you want food and water? And do you want to sleep here tonight?' Out of generosity, they gave it to us. That stranger generosity that we experienced, marked my life to this day," he said.

Growing up, classism divided those who lived in the city from those who live in the village — as those in the city were considered superior.

The generosity of the villagers ruptured Mulumba's way of thinking.

"I looked down on those people who are in villages and I would judge them because they didn't have good shoes, they don't drive cars, and there's no electricity and running water. I harbored this mindset from growing up in the city. But in that moment of need, I saw myself helpless," he said. "I don't know where I would be today if it wasn't for the goodness of strangers."

Arriving in the U.S.

In the late 90s, early 2000s, his mother became a senator — pouring their grief into their community. Due to her political career, the family was targeted, compromising their safety. It forced them to flee to the U.S. and arrive in Oregon.

"She was being targeted but she couldn't just find any other job, because other leaders believed she was apart from the previous regime. They thought she was compromised. So she came here in 2000. She got sponsored with a church called Peace Mennonite Church, that used to be on 106th and Glisan, and we arrived here in 2004. I was 19 years old at the time," he said.

His family started from scratch and worked their way up, learning to adjust and having a hard transition to a foreign place and culture.

"People always smiled at us. In Congo culture, people don't just smile at you. If you are smiling, either you're making fun of me or we are laughing together. There has to be a reason for you to be smiling," he said. "We were shocked by how much people were looking at us and smiling. We couldn't understand that aspect."

Giving back to communities

Mulumba attended college and earned a master's degree in English at Portland State University, eventually meeting his now wife.

He harbored a desire to help others who were once in his shoes. He and his siblings would later go on to join their mother in helping other African refugees and immigrants around them.

"The Congolese refugees that are coming have lived in refugee camps for like 10 years without fathers. There's a lack of male figures," said Mulumba. "My son looks at me and how I behave with his mother and other people in the community and he gets an image of what a man looks like. If I am absent and I don't give him that, he's gonna seek that somewhere."

The African Family Holistic Health Organization team and Mulumba put in many years of work to have a staff and provide resources to African communities. During the pandemic, they provided tutoring and a safe space for young kids, especially boys lacking male figures.

AFHHO community events

The organization has been able to partner with many nonprofits such as Unite Oregon and most recently the City of Portland, which provided funds in partnership with Home Forward, the city's housing authority, to help with rental assistance.

"That has become one of the huge crisis in the community because it's the thing that keeps happening. Holding foreign degrees that they can't use in America puts them in a place where they struggle to get on their feet for a while," said Mulumba.

He said many refugees come to their offices just to vent and be around community.

"Some and others are dealing with PTSD but they don't believe in therapy. We don't have therapists to care for them, but we listen and do what we can to support," he said.

He's worked to put on many community events to spark conversations of healing and implement change for Black immigrants and refugees in Oregon.

Every other month, the organization throws baby showers, gifting over a dozen new and soon-to-be mothers with some essentials. The most recent shower happened in mid-June.

Photos: Baby shower gifts for mothers

AFHHO is always open to have community members join them who are committed to supporting and helping Black immigrant and refugee communities in the Portland metro area.

Mulumba has hopes to not only further grow AFHHO — but for the organization to connect with more Black immigrant and refugee communities and to expand their resources, such as access to therapists in the future.