PORTLAND, Oregon — While you watch your favorite athletes go for gold, consider how all that time, distance, and height is achieved by balancing the same forces all of us mere mortals experience every day.

“Physics is everywhere," said Michael Crosser, a professor at Linfield University.

Crosser's passion for the science draws anyone in. "Knowing that and understanding it helps you appreciate life around you and the beauty of everything around you," he said.

So through the lens of a scientist, we gaze on these 2024 Paris Olympic Games and all the forces at play in an event like discus.

It starts with wind resistance.

"We don't normally think about how we're having to push through all the air around us," Crosser said. "But in discus, for instance, if you throw it at just the right angle and just the right tilt, the air will actually help lift it, elevate it up even higher and make it go a farther distance."

Just the right angles means having the discus tilted slightly higher than the angle of release, moving air faster on the top side, creating lift. With good technique, launching a discus into a headwind actually increases the throw.

Though there is an added complication.

"It's kind of like a top, when you spin a top," said Jacob Slifka, a physics intern and Linfield track and field athlete. "Once it slows down, it kind of wobbles and then it falls. Same with the discus. If it stops spinning, it’s gonna wobble, and turn over."

The solution: spin the discus.

"This gives it angular momentum which helps it maintain its tilt," Crosser said.

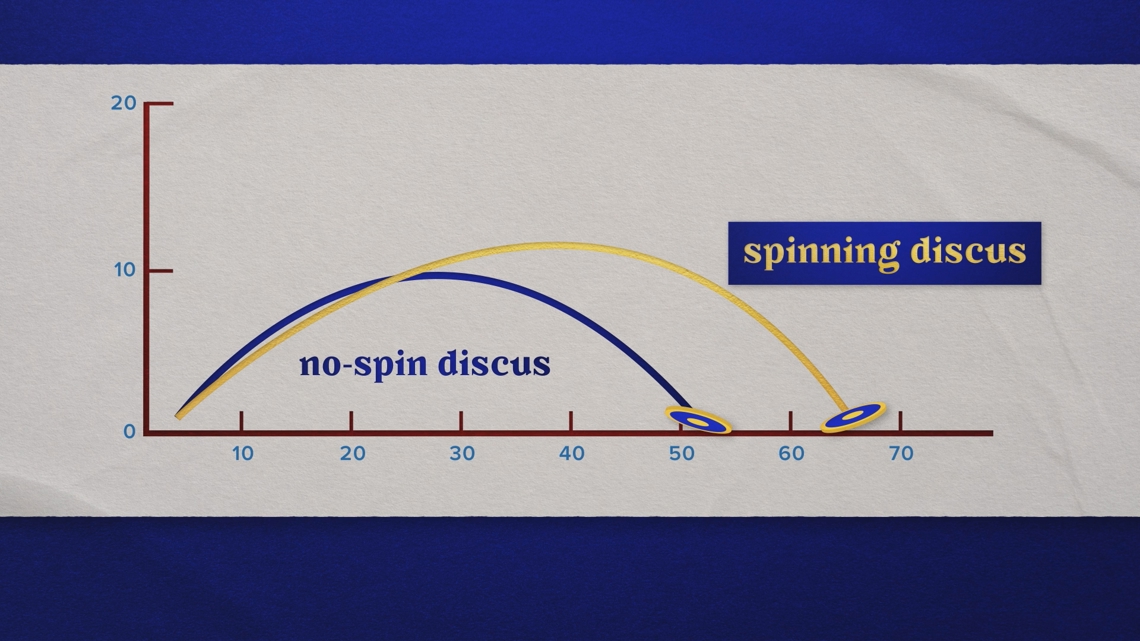

A graph from a 1976 paper published in the Journal of Applied Mechanics shows a difference of 14 meters in throws with spin versus throws without.

Angular momentum is key, just as it is with riding a bicycle, Crosser said.

"If you are rolling, it's easier to keep your balance, but it's almost impossible to stay balanced if you're at a dead stop," he said.

And, here is where physics comes in again. The discus is a uniform weight, but changing the distribution of that weight enables the spin to continue longer.

"It's rim weighted," Slifka said while tossing the discus on campus. "You’ve got a higher moment of inertia on the outside. So once it starts spinning, it's harder to get it to stop."

But, it's not so easy to start the spin, so that's where strength and technique comes into play. But, this higher moment of inertia allows the discus to maintain its spin for longer, and thus, fly farther.

Crosser has a podcast called CrisscrossingScience where he discusses many of the phenomena we all commonly experience. He studies how charges move through atomically thin materials, such as a form of carbon called graphene. Slifka is getting a rare opportunity to do this summer research, and get published, as an undergraduate.