PORTLAND, Ore. — We love our trees in the Pacific Northwest. They are part of our identity.

Oregon has a tree on its license plate. Vancouver calls itself "Tree City USA."

Historically, they have been important to our economy. Trees were also culturally important to Native Americans who lived here before us.

According to Reed College assistant professor, Dr. Aaron Ramirez, the climate in the Pacific Northwest is perfect for growing trees.

"Our climate is conducive to growing really big trees that can live a long time, trees that can grow up to 300 feet tall and live 2,000 years. Our forests store more carbon than any forests in the world," he said.

But, our trees are under duress from climate change. Especially our trees in the city, where temperatures are hotter.

Scientists and students from Portland State University, Reed College, and Washington State University-Vancouver have teamed up to study how climate change is affecting the urban landscape. They're researching what that can tell us about how trees will respond in the rest of the region as the climate warms.

Reed College's Professor Ramirez, along with PSU professors Dr. Paul Loikith and Dr. Todd Rosenstiel, and KGW chief meteorologist Matt Zaffino, appeared on "Straight Talk" to talk about the research.

They told moderator Laural Porter the trees in Portland are like canaries in the coal mine.

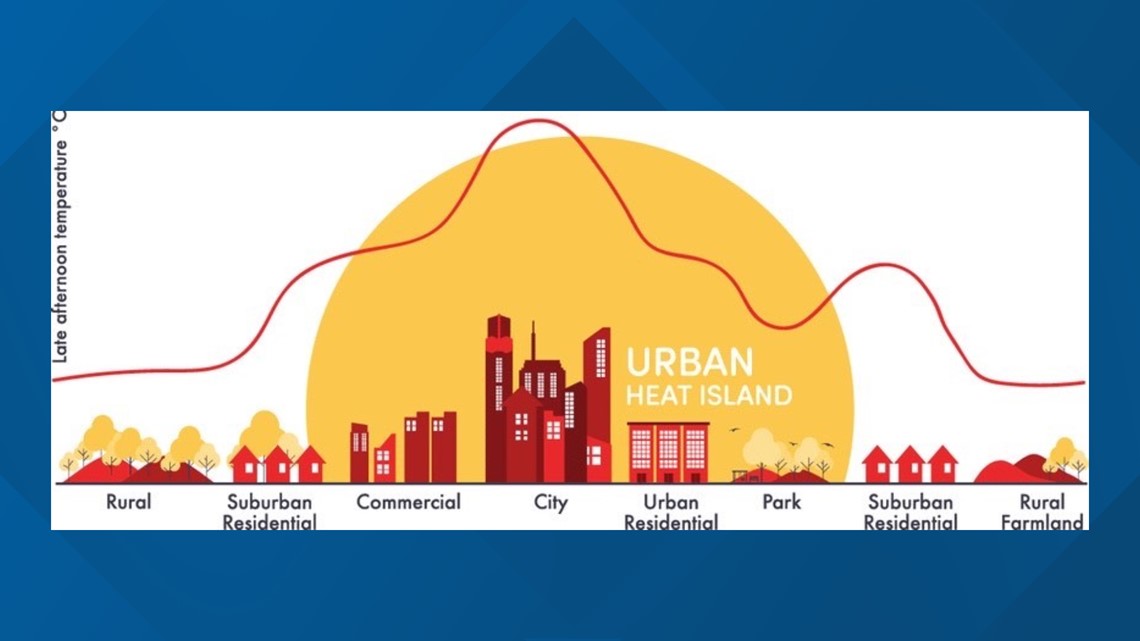

Matt Zaffino described how urban heat islands make temperatures in the city warmer than the surrounding areas.

"I think what we're seeing is the urban heat islands are getting even warmer in a warming climate," he said.

PSU professor Ramirez agreed. He said, "the temperatures trees experience in the city are on par with what we predict for the end of the 21st century."

For scientists, that creates a perfect opportunity.

"I tell my students doing science in the city is like doing science in the future," said PSU professor Todd Rosenstiel.

"Because of elevated temperatures we experience in downtown Portland, the elevated CO2 concentrations, and elevated Ozone concentrations, in many ways, the plants are already living in the future," he said.

Their study will look at how some of Oregon's iconic trees, such as the Douglas Fir, and Red Leaf Maple, will respond to the warming climates that are coming. Professor Ramirez said from their observations so far, it looks like the Western Red Cedar is especially vulnerable.

"People are noticing some die-back of the Western Red Cedar in Portland's Southwest hills," said Rosenstiel.

And in a study test site in Portland's Lents Park, the scientists have noticed previously healthy green trees turning brown. They're working to understand what's causing it, and what it tells us about the future.

The scientists said we're already seeing the impacts of higher temperatures and drought on trees in California and parts of the Southwest.

"We are estimating there are over 400 million dead trees in California's Sierra Nevada and the American Southwest," Ramirez said.

"We haven't seen anything like that in the Pacific Northwest yet, but we are seeing trees impacted by the hotter and drier summers we had, especially in 2015, 2017, and 2018," he said.

"It's hard to overstate the effect of temperatures on what we're talking about when it comes to climate change," said PSU professor Paul Loikith.

Loikith said there is a clear upward trend of hotter temperatures since 1939.

He pointed to 2018 as a year that stands out for the greatest number of days that were 90 degrees or hotter at the Portland airport.

Zaffino also points to 2015 as an extreme year.

"That really stands out in my memory," he said. "We had that stretch of really hot, dry weather from late July to August. We had 20 days in a row. We hit 106 twice."

That was just one degree shy of Portland's all-time record high of 107.

PSU's Professor Loikith said those extreme years are wake up calls about what we will be seeing in the decades to come. The scientists did sound a note of optimism that there is an opportunity to make a difference.

"If we follow lower emission scenarios through the 21st century, the amount and severity of tree killing droughts can be much lower than it would be if we keep those emissions high."

"I think the science is unequivocal. We all have a responsibility to bring down greenhouse gas emissions," said Rosenstiel.

Straight Talk airs Saturday, Feb. 22 and Sunday, Feb. 23 at 6:30 p.m. It's also available as a podcast.